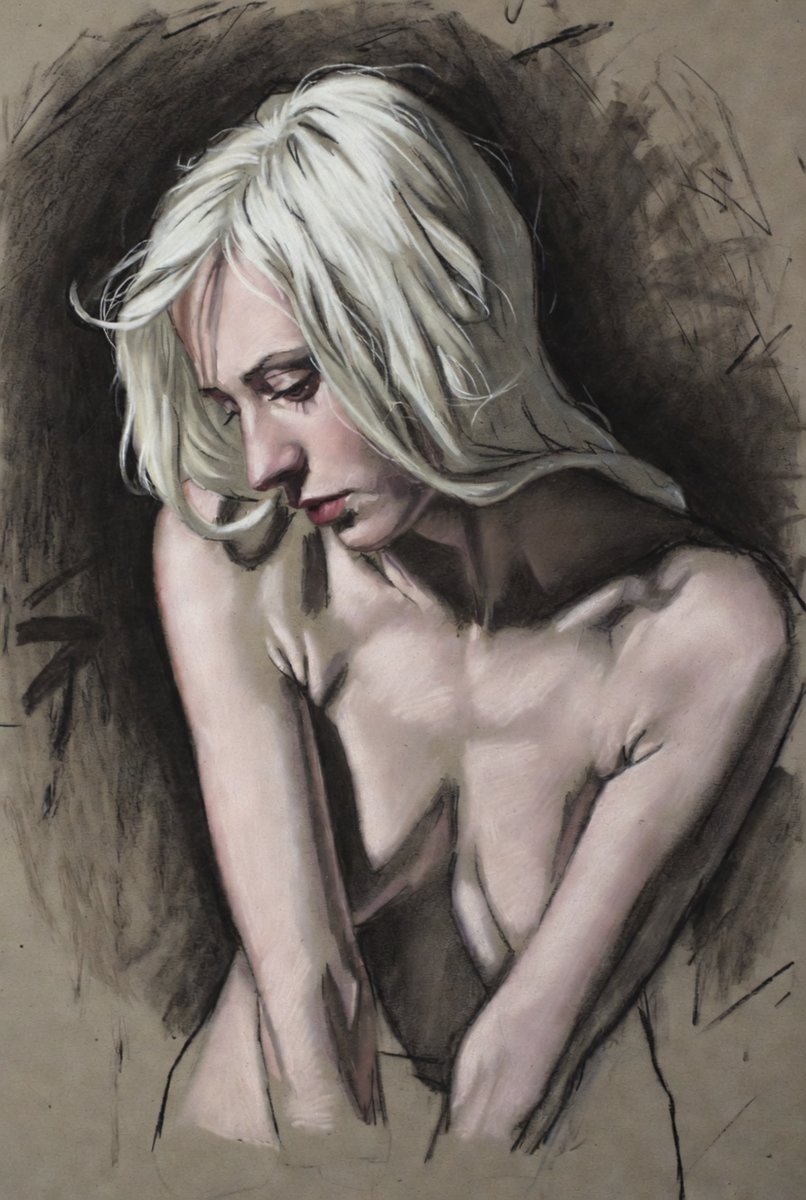

The brothel on the outskirts of Kaiserslautern was never meant to be a theater. Yet Liv Andersson had turned Room 5 into something perilously close. A battered wooden easel stood in the corner, nearly always holding a half-finished charcoal nude that looked unmistakably like her: long limbs, pale skin, head tilted downward in quiet melancholy. The walls formed a chaotic gallery. Sketches hung pinned next to torn pages from old Filmkritik issues, stills of Liv Ullmann’s haunted face in Persona, Bibi Andersson’s defiant gaze in The Seventh Seal, and a large, yellowed poster of Bergman’s Wild Strawberries, rescued from a skip behind a Düsseldorf cinema. On the dresser sat a small reel-to-reel tape player, forever threaded with a crackling bootleg of Max von Sydow delivering the knight’s monologue about playing chess with death. Liv permitted only candlelight, insisting that electric bulbs flattened the soul.

She had draped the bed in black linen dyed by hand. Sandalwood incense drifted through the room, trying without much success to cover the stubborn smells of bleach, sweat, and cheap cologne that rose through the floorboards from years of steady use. A small mirror framed with tiny bulbs, salvaged from a bankrupt cabaret, completed the illusion. When a client stepped inside, he entered not a brothel room but a dimly lit stage where Liv waited already in character: tragic Nordic muse, suffering artist, woman teetering on the edge of some profound revelation.

She told the same story so often that it had hardened into private doctrine. “This is temporary research,” she would say in her careful, lightly accented German, blue eyes wide and earnest. “Material for my thesis at the Kunstakademie: ‘The Female Body as Commodity and Canvas in Late Capitalist Society.’” The other women rolled their eyes with fond exasperation; Frau Metzger just grunted and noted the tuition excuse in her ledger. In truth, the money went toward oil paints, stretched canvases, turpentine, modeling fees, and the climbing rent on her small Düsseldorf flat. The simpler, more painful reality was that Liv needed the fantasy of being discovered the way some people need faith.

It started innocently two years earlier. A visiting professor from Stockholm screened her short super-8 film, an experimental eight-minute piece shot in a snow-covered forest near Malmö: a lone woman walking in circles while a voice-over murmured fragments about silence and speech. Afterward, he compared her presence on screen to “early Ullmann, before the mannerisms took hold.” The remark lodged in her like a thorn. If one academic could see it, surely a real director would too. And what better place to be found than the most improbable one? The brothel drew men who liked to claim connections: producers on holiday, scouts for European co-productions, the occasional Swedish businessman with “friends in Stockholm.” Fate, she decided, thrived on irony.

At twenty-three, Liv was tall and almost luminous, white-blonde hair worn loose like a silent-film star, body seemingly fragile until you noticed the quiet strength in her arms from hours of stretching canvas. She moved with deliberate grace, every gesture shaped for an invisible lens. Clients loved the act; they paid well to believe they were sleeping with a tormented Scandinavian genius who had briefly fallen among ordinary men.

The obsession grew slowly. Between appointments, she read Bergman biographies, memorized monologues, and practiced glycerin tears in the mirror until they flowed on command. She started calling certain clients “Herr Director” in bed, the words half joke, half prayer. When no savior arrived, she told herself the timing was wrong. The right man simply had not yet walked through the door.

He finally appeared on a Thursday evening in March 1983.

Downstairs, the bar was dense with cigarette smoke and restless chatter. David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” thumped from the jukebox while American airmen from Ramstein, still wired from the recent Able Archer exercises, drank beer and debated whether the Soviets had genuinely feared a NATO first strike. Rumors circulated: intercepted signals, near-misses in the Baltic. Frau Metzger counted marks behind the counter with brisk efficiency. Hanno quietly swapped a flickering bulb above the pool table, his large hands calm and precise.

The madam appeared at Liv’s door wearing an expression that mixed amusement with caution. “Special request from downstairs. Older gentleman, Swedish accent, well-dressed. Claims he was the gaffer on Winter Light. Asked for the ‘Nordic girl who understands art.’ Paid double upfront and left these.” She extended a small bouquet of slightly wilted hothouse roses, obviously grabbed in a hurry from the Turkish florist near the station. “Try not to collect an Oscar during the performance tonight.”

Liv’s heart gave a clean, sharp triple beat. She lit every candle, cued the tape to the precise instant von Sydow pleads with Death for more time, and slipped into a sheer white slip that might have come straight from Cries and Whispers. When the knock sounded, polite and almost tentative, she opened the door fully in role: head tilted in sorrow, one hand braced on the frame, eyes shining with carefully rehearsed pain.

The man who entered was about sixty, with thin gray hair neatly combed, wire-rimmed glasses catching the candle glow, a camel-hair coat carrying faint traces of aquavit and old theater seats. He held the roses like an offering.

“Fröken Andersson,” he said with a small, formal bow, his Swedish crisp and old-fashioned. “I am Herr Lindström. I was the chief electrician, gaffer, on Winter Light in 1962. Ingmar himself praised my shadows.”

Liv felt the floor shift. She took his coat with reverent hands and guided him inside as though ushering in a minor saint.

They did not hurry. Lindström settled into the room’s only wooden chair while Liv lowered the light to one candle and launched into a breathless passage from Persona, shifting fluidly between Swedish and German, voice breaking at exactly the right moments. He watched, entranced, murmuring “Ja… precis… the isolation, the pain…” as she drifted through the small space like a specter, slip clinging to pale skin, arms reaching in mute appeal.

She knelt before him slowly, almost worshipfully, opening his trousers with the gravity of unveiling something holy. When she took him in her mouth, she looked up with wide, suffering eyes, glycerin tears catching the light. Lindström stroked her hair and quoted back to her, “Are you afraid of death?” his voice thick with feeling and mounting desire.

When he finally led her to the bed, it felt like ceremony. He entered her missionary-style, deliberate and slow, gaze locked on hers as though framing the perfect close-up. Liv arched and whispered lines from The Silence, body answering with practiced accuracy while her mind raced ahead: this was it, the recognition she had rehearsed in countless solitary nights. She came with a dramatic cry that recalled Ullmann’s most shattering breakdowns; Lindström followed soon after, breathing “Magnificent… pure cinema…” against her throat.

They lay side by side in the unsteady light afterward, sharing a cigarette while the tape played the knight’s confession about life’s emptiness. Lindström spoke of Bergman’s brilliance, of late nights on Fårö, of recognizing true talent when it appeared. He promised introductions to “serious people in Stockholm, producers who still value artistry.” Liv’s mind flared with images: auditions in Gamla Stan, a premiere at Cannes, Kaiserslautern left behind forever.

He came back the next week, then the week after, always with roses and a hidden bottle of aquavit. Each visit grew more theatrical. One night, she staged the hospital scene from Persona, lying stiff and mute while he touched her, only murmuring Elisabet’s silent thoughts when she broke character; another time, she posed nude on the black sheets like the chess player facing Death, letting him adjust her limbs while she stared into the bleak distance. He praised her endlessly: “You have the soul Ingmar looked for in every actress.” She believed him completely.

Between his visits, she painted feverishly: Lindström as the knight, as von Sydow on the beach, as Bergman bent over a script. She wrote letters to the Swedish Film Institute, enclosing blurry stills from her Super 8 film, mentioning “a mentor who worked closely with Bergman.” Hope burned bright and constant.

It shattered on a rainy April night when thunder rolled across the Pfalz like distant guns. Lindström arrived late, coat drenched, eyes bloodshot, clutching a half-empty bottle of aquavit instead of flowers. They ran through the ritual: lowered lights, monologue, glycerin tears. But halfway through the staged intimacy, he broke, weeping hard against her shoulder.

“I lied,” he slurred. “I carried cables one day on Winter Light. I was twenty, a junior grip, nothing else. Bergman never knew who I was. The ‘praise’ was just the head electrician saying I hadn’t dropped a lamp.”

Liv went still beneath him, his confession heavier than his weight. “But you said—”

“I wanted it to be true,” he whispered, tears soaking her skin. “For you. For me. You perform so beautifully when you believe.”

The ridiculousness hit her like cold water. All the rehearsals, the tears, the carefully built anguish, for a retired municipal lighting technician from Uppsala who had spent one meaningless day on a masterpiece twenty-one years earlier and built his whole identity around it.

She laughed, sharp and sudden, almost mean. Lindström laughed too, choking through sobs, and for a moment they were simply two foolish people in a candlelit brothel room, naked, absurd, and completely human.

She did not take his money that night. Instead, she poured the rest of the aquavit into teacups and listened while he talked about his failed marriage to a woman who despised films, his years hanging streetlights in Göteborg, his quiet evenings rewatching Bergman on a fuzzy television, still convinced he had once touched greatness. When he left, unsteady in the rain, he pressed the wilted roses into her hand and apologized “for the bad script, fröken.”

Liv stayed among the guttering candles until the storm quieted and dawn paled the window. She looked at her sketches of him as a cinematic hero, then turned each one to the wall.

The next evening, she worked as usual: an American captain from Ramstein who wanted plain sex, no theatrics, no dialogue. She gave it efficiently, without monologues or tears or existential weight. Afterward, she extinguished every candle, boxed the reel-to-reel, and took down the Wild Strawberries poster, rolling it gently as though burying something loved.

Frau Metzger noticed when Liv came down for coffee. “No more Ingmar tonight?”

Liv gave a small, weary smile that felt unexpectedly light. “I got my close-up. Turns out the director was strictly amateur.”

Downstairs, Dani counted her Hollywood savings with narrow, knowing eyes; Ayla laughed at a Turkish trucker’s joke; Marta smoked in silence, staring at nothing; Ilse nursed a flat beer. Hanno crossed the bar carrying a new bulb for the hallway, pausing just long enough to meet Liv’s gaze through the open door to her now-bare room. He nodded once, a quiet recognition of something private, then moved on with his steady pace.

Liv went back to Room 5 and opened the windows to let in the clean, rain-washed air. She kept painting, the work sharper now, less theatrical, figures that looked straight at the viewer instead of past them into tragic distance. She still dreamed of cinema sometimes, but she no longer waited for rescue to arrive, wearing the mask of recognition.

Some nights she left one candle burning. Not for atmosphere or performance, just because she liked the way the flame moved: honest, unscripted, alive.